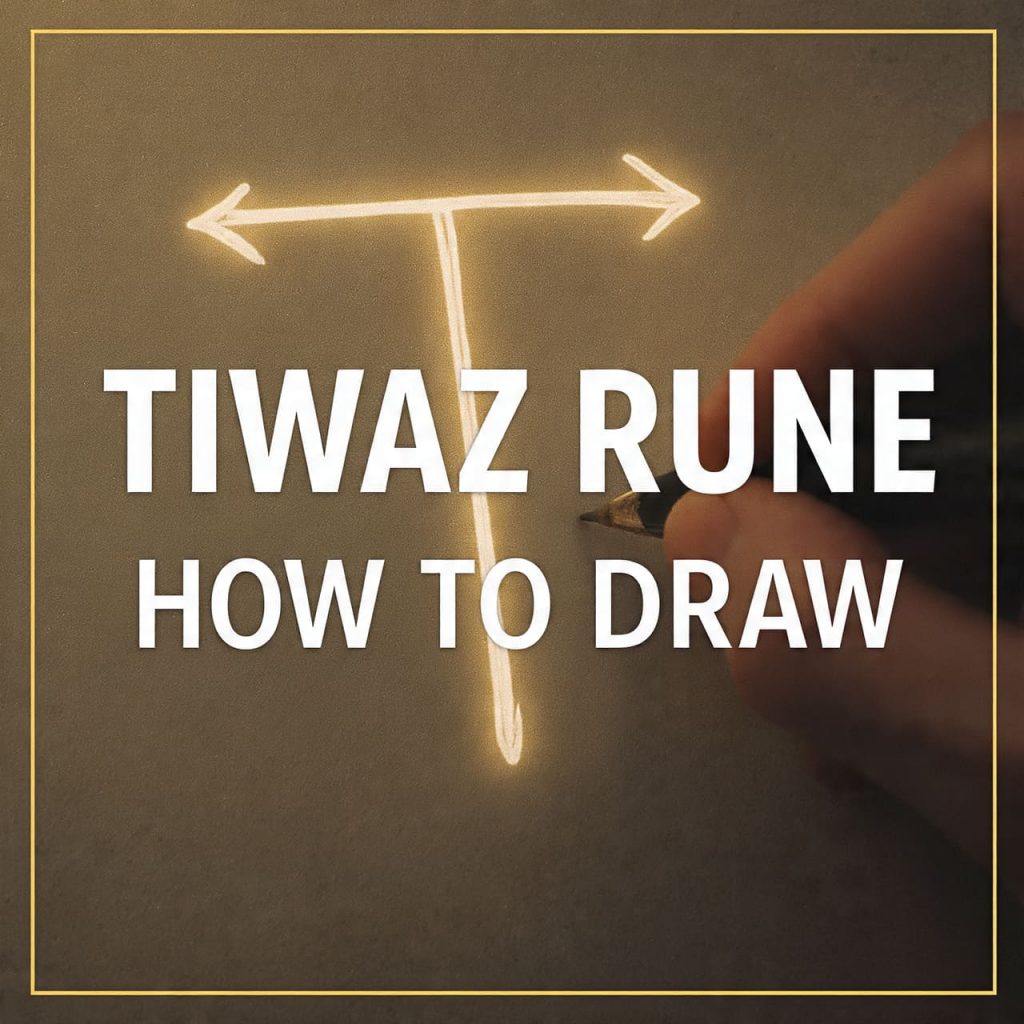

Modern guides frequently present the Tiwaz rune as having a single, correct way to draw it, often illustrated with clean lines and fixed proportions. This presentation suggests that early runic users followed standardized drawing rules comparable to those of modern alphabets or symbolic systems. Historically, this assumption is problematic. The question is not whether people today draw Tiwaz in a consistent way, but whether early evidence supports the existence of an authoritative or prescribed drawing form.

💜 Need a clear answer right now?

CONSULT THE YES OR NO TAROT Free · No registration · Instant resultThe uncertainty here is factual and methodological. Evaluating it requires examining archaeological variation rather than relying on modern conventions.

Applying evidence-first historical reasoning, including comparative approaches discussed by astroideal, allows the issue to be assessed without importing later expectations.

Although many readers consult qualified professionals for contemporary explanations, historical conclusions must be grounded in archaeology, epigraphy, and early context.

The guiding question of this article is deliberately narrow and binary: does the historical record support a single, correct way to draw the Tiwaz rune in its original context, yes or no?

What “How to Draw” Means as a Historical Claim

In historical writing systems, “how to draw” implies recognized conventions governing form, orientation, and execution. For such conventions to be historically demonstrable, evidence would need to show consistency across inscriptions, correction of deviations, or instructional material explaining proper form.

This definition does not deny that early rune carvers produced recognizable shapes. It establishes the evidentiary threshold required to claim that one form was considered correct. Modern explanations circulated by reliable readers often assume standardization by analogy with later scripts, but early runic writing must be evaluated on its own material evidence.

Tiwaz Within the Elder Futhark

Tiwaz belongs to the Elder Futhark, the earliest reconstructed runic alphabet, used by Germanic-speaking communities roughly between the second and eighth centuries CE. The alphabet itself is reconstructed from recurring inscriptional patterns rather than preserved manuals or orthographic guides.

Within inscriptions, Tiwaz functions as a phonetic character representing a /t/ sound. Its basic visual identity is recognizable, but its exact shape varies. Modern diagrams that present one definitive outline often resemble later symbolic systems discussed alongside online tarot sessions rather than early medieval writing practice.

Archaeological Evidence of Tiwaz Forms

Archaeological evidence provides the strongest basis for assessing how Tiwaz was drawn. The rune appears in inscriptions carved on stone, metal, bone, wood, and other materials across a wide geographic area.

What this evidence shows is variation. Some forms are sharply angular, others slightly curved. Stroke length, angle, and symmetry differ depending on the carving surface and tool used. Importantly, these variants are all understood as the same rune within their inscriptions. There is no indication that one form was preferred or that deviations were considered incorrect. Later visual standardization, similar in structure to modern video readings, does not reflect early material practice.

Orientation and Directional Flexibility

Another common assumption is that Tiwaz must be drawn in a specific orientation. Archaeological evidence contradicts this. Runes were carved to fit available space, object shape, and writing direction. Inscriptions may run left-to-right, right-to-left, vertically, or along curved surfaces.

As a result, Tiwaz appears rotated or mirrored in some contexts without any apparent change in function. There is no evidence that orientation affected correctness or meaning. This flexibility suggests that recognizability, not strict orientation, was the primary concern. Modern insistence on fixed orientation mirrors later symbolic systems rather than historical runic practice.

Absence of Instructional or Normative Texts

A decisive limitation in answering how to draw Tiwaz is the absence of instructional texts. No surviving sources from the Elder Futhark period describe how runes should be formed, proportioned, or taught.

In writing traditions where precision of form mattered, teaching aids or corrective practices often survive. The lack of such material for runes is historically significant. It suggests that variation was acceptable as long as the character remained legible. Attempts to impose drawing rules often rely on later analogies structurally similar to those used in phone readings rather than on early evidence.

Medieval Sources and Their Limits

Medieval rune poems and related texts are sometimes cited in discussions of rune form. These sources date centuries after the Elder Futhark period and reflect different linguistic and cultural contexts.

Importantly, they do not describe how runes were drawn. They offer descriptive phrases rather than orthographic guidance. Using them to justify specific drawing methods conflates medieval literary tradition with early runic practice.

Modern Standardization and Its Origins

Standardized drawings of the Tiwaz rune emerge primarily in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. During this period, scholars and educators sought to catalog runes systematically, often selecting a single representative form for clarity.

These selections were practical and pedagogical, not historical. They reflect modern needs for consistency rather than ancient consensus. Similar processes of standardization occur in other modern symbolic frameworks, including generalized horoscope insights, where uniformity is imposed for usability rather than inherited from antiquity.

Evaluating Common Claims About Correct Form

Beginners are often told that Tiwaz has a correct shape that must be drawn accurately to be valid. Evaluating this claim requires returning to the evidence.

- Archaeology shows multiple accepted forms.

- Orientation varies without consequence.

- No inscriptions indicate correction or error.

- No texts prescribe drawing rules.

- Standard forms appear only in modern reconstructions.

- Even when modern presentations integrate Tiwaz into systems such as love tarot readings, these reflect contemporary synthesis rather than early convention.

- Comparative evaluation using methods discussed by astroideal reinforces this assessment.

These points do not deny that modern standards exist. They clarify that those standards are modern, not ancient.

Evaluating the Core Claim with Evidence

The core claim addressed here is that there is a historically correct way to draw the Tiwaz rune. Archaeological variation, combined with the absence of normative guidance, argues against this claim.

The evidence supports a clear conclusion: no, the historical record does not support the existence of a single, correct way to draw the Tiwaz rune in its original context.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is there one correct way to draw Tiwaz?

No, historical evidence shows multiple accepted forms.

Do inscriptions show drawing mistakes?

No evidence suggests forms were considered incorrect.

Was Tiwaz orientation fixed?

No, orientation varies depending on space and material.

Are modern diagrams historically accurate?

They are simplified reconstructions, not ancient standards.

Did early sources explain how to draw runes?

No instructional texts survive from the period.

Can Tiwaz forms vary by region?

Yes, regional and material variation is well documented.

Call to Action

When encountering claims about how to draw the Tiwaz rune, evaluate whether those claims are supported by archaeological or textual evidence. This approach allows you to get a clear yes or no answer grounded in documented history rather than assumption.