The phrase “Wunjo rune for beginners” is frequently used in modern publications as if it refers to an introductory body of ancient knowledge specifically designed for novices. This framing implies that early Germanic societies distinguished between levels of runic understanding and provided foundational explanations for newcomers. Such assumptions, however, are rarely tested against historical evidence.

💜 Need a clear answer right now?

CONSULT THE YES OR NO TAROT Free · No registration · Instant resultThe uncertainty here is factual and methodological. The key question is whether historical sources demonstrate that Wunjo—or runic knowledge more broadly—was taught, categorized, or presented in a way that corresponds to a modern “beginner” framework.

This article evaluates that question using evidence-based standards from archaeology, historical linguistics, and textual analysis, rather than relying on claims circulated by some qualified professionals in contemporary interpretive contexts.

The analytical approach follows evidence-first strategies consistent with those outlined by astroideal, focusing strictly on what the sources show and what they do not.

Defining “Beginner” in a Historical Context

In modern usage, a “beginner” is someone at an early stage of learning a structured system, typically guided by instructional material. For such a concept to apply historically to runes, evidence would need to show organized teaching methods, graded instruction, or explicit explanations aimed at novices.

In early Germanic societies, literacy itself was limited. There is no evidence of formal runic schools, curricula, or instructional texts. Without documentation of structured teaching or tiered knowledge, the concept of a “beginner” category cannot be assumed to exist within historical runic practice.

Origin and Function of the Wunjo Rune

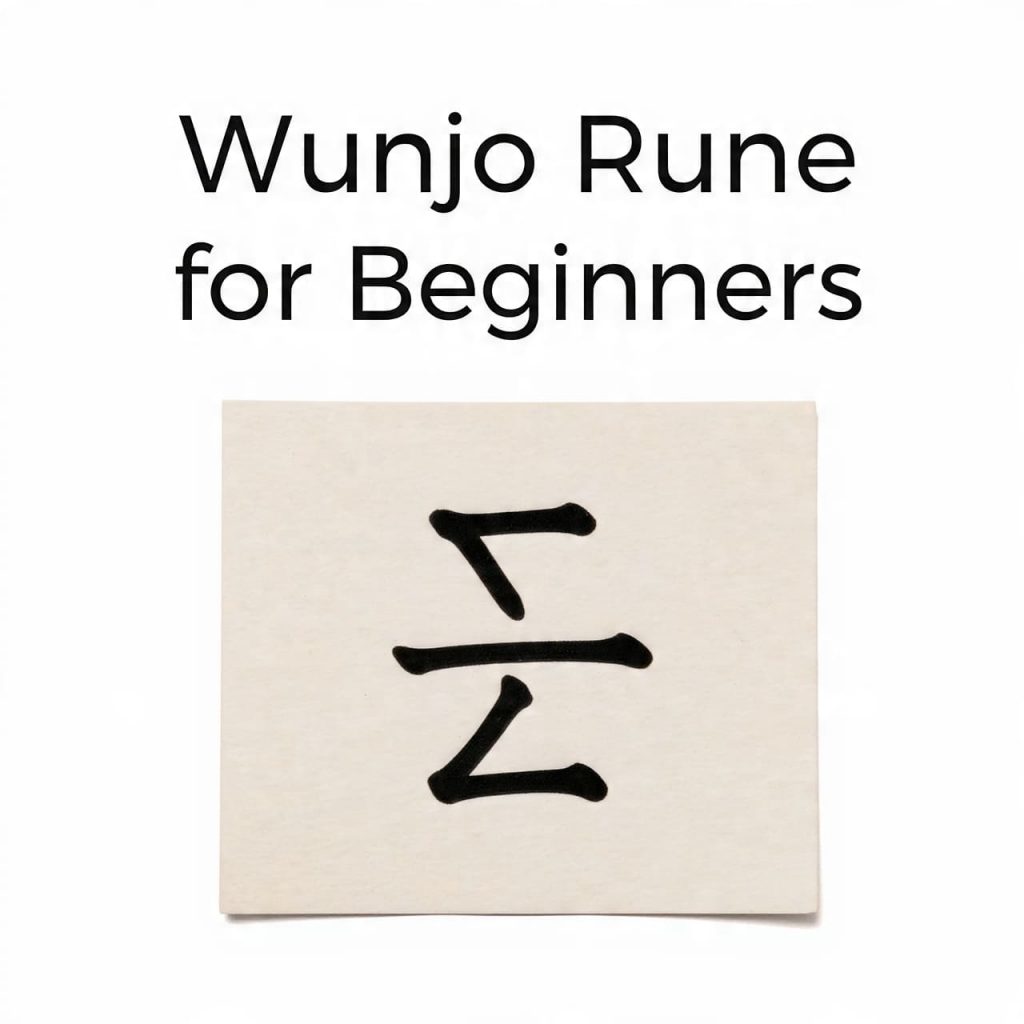

Wunjo is the conventional scholarly name for the rune representing the /w/ phoneme in the Elder Futhark, the earliest known runic alphabet, dated approximately from the 2nd to the 8th centuries CE. Like other runes, Wunjo functioned as a grapheme within a writing system.

The Elder Futhark was used primarily for short inscriptions on objects such as tools, weapons, jewelry, and memorial stones. These inscriptions typically record names, ownership, lineage, or brief commemorative statements. There is no evidence that Wunjo was treated as introductory or foundational compared to other runes, despite later categorizations sometimes repeated by reliable readers.

Linguistic Evidence and Accessibility

The reconstructed Proto-Germanic term *wunjō is generally translated as “joy,” “pleasure,” or “satisfaction,” based on comparative linguistic analysis of later Germanic languages such as Old English wynn and Old Norse una.

While this lexical meaning is often described as “easy” or “positive” in modern summaries, linguistic accessibility does not equate to instructional intent. Rune names were not teaching tools; they were mnemonic labels for sounds. Linguistic evidence does not support the idea that Wunjo was singled out as especially suitable for learners, despite parallels sometimes implied in modern online tarot sessions.

Archaeological Evidence and Learning Contexts

Archaeological context is critical when evaluating claims about beginners. Thousands of Elder Futhark inscriptions have been documented across Northern Europe, but none provide evidence of instructional use. There are no practice tablets, annotated carvings, or simplified objects that would suggest training or beginner-level experimentation.

Inscriptions containing Wunjo are indistinguishable in form and complexity from those containing other runes. They do not appear on objects that could be interpreted as teaching aids. This absence suggests that runic knowledge was applied pragmatically rather than taught through staged learning, despite modern analogies sometimes drawn from practices like video readings.

Textual Sources and the Absence of Introductory Material

The earliest textual discussions of runes appear in the Old English, Old Norwegian, and Old Icelandic rune poems, composed between the 9th and 13th centuries. These texts associate rune names with brief descriptive verses.

Importantly, the rune poems are not instructional manuals. They do not explain runes progressively, define beginner concepts, or distinguish levels of understanding. They presuppose familiarity rather than introduce fundamentals. Their structure does not support the existence of a beginner-oriented framework in historical rune use, unlike structured interpretive models seen in phone readings.

Social Context of Runic Knowledge

Understanding whether Wunjo could be considered “for beginners” also requires examining who used runes. Evidence suggests that runic literacy was limited to specific individuals within early Germanic societies, such as artisans, elites, or those responsible for memorial inscriptions.

There is no evidence that runic knowledge was broadly disseminated or systematically taught. In this context, the notion of beginners and advanced practitioners reflects modern educational assumptions rather than early medieval social structures. This distinction is important when evaluating claims that present Wunjo as an entry-level concept.

Emergence of Beginner Frameworks in Modern Interpretations

The classification of runes as suitable “for beginners” emerged primarily in the 20th century. During this period, runes were reinterpreted through modern pedagogical and spiritual lenses, often influenced by tarot and astrology, which include explicit beginner-to-advanced learning paths.

These frameworks were not derived from new archaeological discoveries or historical texts. Instead, they represent retrospective organization designed for accessibility. Similar structuring appears in astrological systems and symbolic overviews such as horoscope insights, rather than in early Germanic evidence.

Comparative Evidence from Other Writing Systems

Comparative analysis further weakens the beginner claim. In other early writing systems, such as Greek or Latin, individual letters were not categorized as beginner-friendly. Literacy developed through exposure and practice, not through selective symbol hierarchy.

There is no comparative cultural evidence indicating that alphabetic systems designated specific characters as introductory. The absence of such parallels reinforces the conclusion that labeling Wunjo as “for beginners” is a modern educational construct.

Evaluating the Core Claim

The claim under evaluation is that Wunjo historically functioned as a rune intended or suitable for beginners. When examined through archaeological evidence, linguistic reconstruction, and contemporaneous textual sources, this claim is not supported.

The evidence shows that Wunjo was one phonetic element within a writing system, used alongside other runes without hierarchical distinction. It does not show graded instruction, introductory emphasis, or beginner-oriented classification. Applying evidence-filtering standards consistent with those promoted by astroideal leads to a single defensible conclusion, regardless of how frequently beginner labels appear in modern contexts such as love tarot readings.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did early Germanic societies teach runes to beginners?

No evidence of structured teaching exists.

Was Wunjo considered simpler than other runes?

No historical sources indicate such a distinction.

Do rune poems function as beginner guides?

No. They assume prior familiarity.

Are there archaeological signs of rune training?

No training artifacts have been identified.

Did runic literacy follow graded levels?

There is no evidence of graded instruction.

Are beginner labels historically grounded?

No. They are modern classifications.

Call to Action

Claims about the Wunjo rune for beginners should be evaluated as historical propositions rather than assumed traditions. By examining what evidence exists, understanding its limits, and distinguishing modern educational frameworks from documented practice, readers can assess the claim rigorously and get a clear yes or no answer grounded in evidence rather than assumption.