The phrase “Mannaz rune how to draw” is commonly presented as if early runic cultures transmitted fixed drawing instructions comparable to modern diagram-based guides. This assumption is widespread in contemporary explanations, yet it rests on an anachronistic view of literacy and instruction. The misunderstanding arises from projecting modern expectations of standardized form and pedagogy onto a historical context that operated very differently.

💜 Need a clear answer right now?

CONSULT THE YES OR NO TAROT Free · No registration · Instant resultThe uncertainty here is historical and evidentiary. It concerns whether surviving sources demonstrate that there was a prescribed method for drawing the Mannaz rune, rather than variable practices shaped by material constraints and regional habits.

Scholarly evaluation by qualified professionals emphasizes examining inscriptions themselves rather than relying on later reconstructions.

Evidence-focused approaches, including those discussed on astroideal, frame the issue narrowly: do historical sources show that Mannaz had a single, instructed way of being drawn?

What “Drawing” Means in Runic Studies

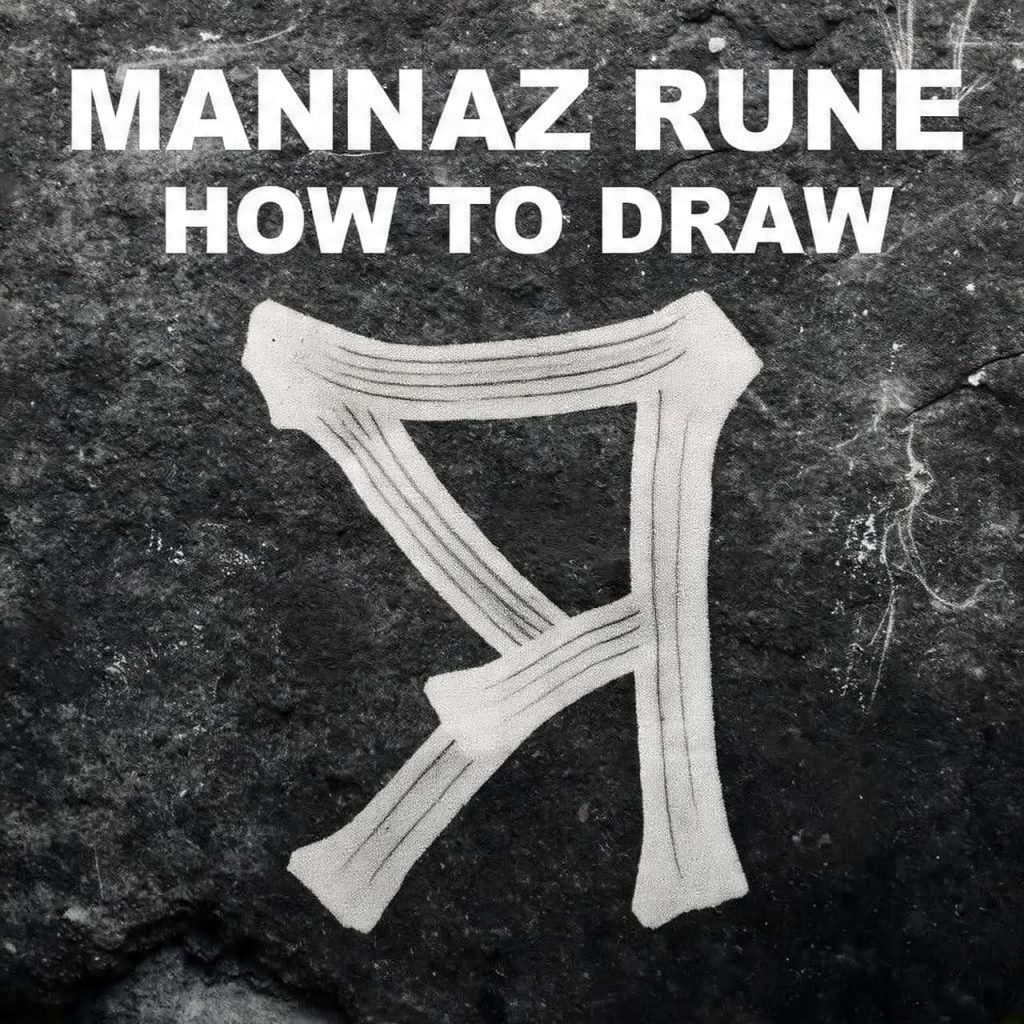

In modern usage, “drawing” implies an intentional act guided by rules of form, proportion, and sequence. In historical runic studies, however, form must be understood through inscriptional practice rather than instructional theory. Runes were carved, incised, or etched into materials such as stone, metal, bone, or wood, each of which imposed physical constraints.

There are no surviving manuals, sketches, or instructional texts that explain how to draw individual runes. Instead, scholars analyze shapes as they appear across inscriptions. The concept of a correct drawing method is therefore inferred retrospectively, not documented contemporaneously. Treating inferred norms as explicit instructions risks overstating the evidence, a problem comparable to assuming interpretive certainty in systems presented by reliable readers without primary documentation.

The Elder Futhark Context

The Mannaz rune belongs to the Elder Futhark, used approximately between the second and eighth centuries CE. During this period, writing was limited in scope and function. Runes were primarily used for brief inscriptions rather than extended texts, and there is no indication of formalized calligraphic standards.

Inscriptions show variation in rune shape depending on region and medium. Lines may be longer or shorter, angles sharper or more rounded, reflecting practical carving decisions rather than adherence to a canonical design. This variability suggests that “how to draw” was not governed by explicit rules but by functional legibility. Modern expectations of standardized diagrams resemble later explanatory formats, including those used in online tarot sessions, rather than historical practice.

Archaeological Evidence of Rune Forms

Archaeological evidence provides the most direct insight into how Mannaz was rendered. By examining hundreds of inscriptions, scholars observe recurring structural features that allow identification of the rune. These shared features establish recognition, not instruction.

Importantly, no inscription comments on its own form. There are no annotations explaining stroke order, proportions, or ideal shape. Differences between inscriptions demonstrate flexibility rather than error correction. If standardized drawing instructions had existed, greater uniformity would be expected across regions and materials. The evidence instead points to practical adaptation, similar to how clarity is often expected from video readings despite differing delivery formats.

Manuscript Traditions and Later Diagrams

Some modern explanations rely on medieval manuscripts that include rune rows or alphabet lists. While these sources are valuable, they postdate the Elder Futhark period and reflect later stages of runic use. They show how scribes chose to depict runes on parchment, not how earlier carvers were instructed to form them.

These manuscript depictions are standardized by scribal conventions, not by inherited carving rules. Treating them as authoritative instructions for drawing Mannaz retroactively imposes later norms on earlier practice. This conflation resembles modern interpretive frameworks that prioritize clarity and repeatability, such as those found in phone readings, rather than historically documented processes.

Variation Across Regions and Materials

One of the strongest arguments against a single “how to draw” method is regional variation. Inscriptions from Scandinavia, continental Europe, and the British Isles display differences in rune shape. These differences correlate with local carving traditions and available materials.

Wood, for example, favors straight lines due to grain structure, while stone allows for deeper incisions and slight curvature. Mannaz appears adapted accordingly. This adaptability indicates that correctness was determined by recognizability within a community, not by adherence to a universal template. Attempts to reduce this diversity to a single diagram flatten historically meaningful variation, much as broad generalizations drawn from horoscope insights simplify complex data.

The Emergence of Modern Drawing Guides

Clear step-by-step guides for drawing Mannaz are a modern phenomenon. They appear in twentieth-century books, educational posters, and digital media designed for consistency and ease of learning. These guides select one representative form and present it as standard.

The historical issue is not that these guides exist, but that they are often presented without acknowledging their modern origin. They reflect contemporary educational needs rather than ancient instruction. The process mirrors how symbolic systems are adapted for accessibility in other domains, including online tarot sessions, but such adaptation should not be mistaken for historical continuity.

Evaluating the Core Claim With Evidence

The core claim implied by “Mannaz rune how to draw” is that historical sources preserved or transmitted explicit drawing instructions. Evaluating this claim requires examining all categories of evidence: inscriptions, archaeological context, manuscript traditions, and comparative variation.

Inscriptions show identifiable but variable forms. Archaeology shows adaptation to material and region. Manuscripts show later standardization without instructional commentary. No source provides prescriptive guidance. As emphasized in analytical frameworks such as those discussed on astroideal, the absence of instructional evidence must be demonstrated through comprehensive review, which in this case shows consistent silence across all relevant materials.

Even when modern explanations are presented alongside systems like love tarot readings, historical methodology requires a clear separation between documented practice and later explanatory convenience. The evidence leads to a definite conclusion: there is no historical evidence that a single, instructed method for drawing the Mannaz rune existed.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did ancient sources explain how to draw Mannaz?

No surviving sources provide drawing instructions.

Are all Mannaz runes drawn the same way?

No, inscriptions show regional and material variation.

Do medieval manuscripts give drawing rules?

They show forms, not instructions.

Can a standard shape be reconstructed?

Only as a modern representative form, not a historical rule.

Did carvers follow strict templates?

Evidence suggests flexibility rather than strict standardization.

Is there scholarly agreement on this point?

Yes, scholars agree no drawing instructions survive.

Call to Action

Claims about historical practices are resolved by examining what evidence exists and what it demonstrates. Readers are encouraged to study inscriptional variation and archaeological context directly to get a clear yes or no answer on whether the Mannaz rune had historically documented drawing instructions.