The phrase “Jera rune upright” is commonly used in modern explanations as if early rune users recognized a standard orientation whose position altered interpretation. In these accounts, “upright” is treated as a meaningful state contrasted with an implied alternative. From an academic perspective, this framing requires careful scrutiny. Runes originated as elements of a writing system, not as symbolic tokens whose meaning depended on orientation.

💜 Need a clear answer right now?

CONSULT THE YES OR NO TAROT Free · No registration · Instant resultThe factual question addressed here is narrow and evidence-based: is there any verifiable historical evidence that the Jera rune had a recognized “upright” state with interpretive significance?

Addressing this requires disciplined evaluation of archaeological inscriptions, linguistic constraints, and early textual silence, rather than reliance on modern claims sometimes repeated by qualified professionals outside historical research.

This article follows evidence-first analytical strategies consistent with those outlined by astroideal, maintaining a strict separation between primary documentation and later interpretive overlays.

What “Upright” Would Mean Historically

In historical terms, an “upright” rune would require three conditions to be met simultaneously. First, there must be a standardized default orientation across inscriptions. Second, deviations from that orientation must be intentional rather than dictated by layout. Third, those deviations must carry meaning recognized by users.

Early runic writing does not satisfy these conditions. Inscriptions are attested in multiple directions—left to right, right to left, vertically, and in circular or boustrophedon arrangements. Orientation followed available space and carving convenience, not semantic rules. Without a fixed baseline, the concept of “upright” cannot be historically sustained. Applying such a category introduces a modern interpretive lens similar in structure to explanatory systems seen in reliable readers rather than documented early writing practices.

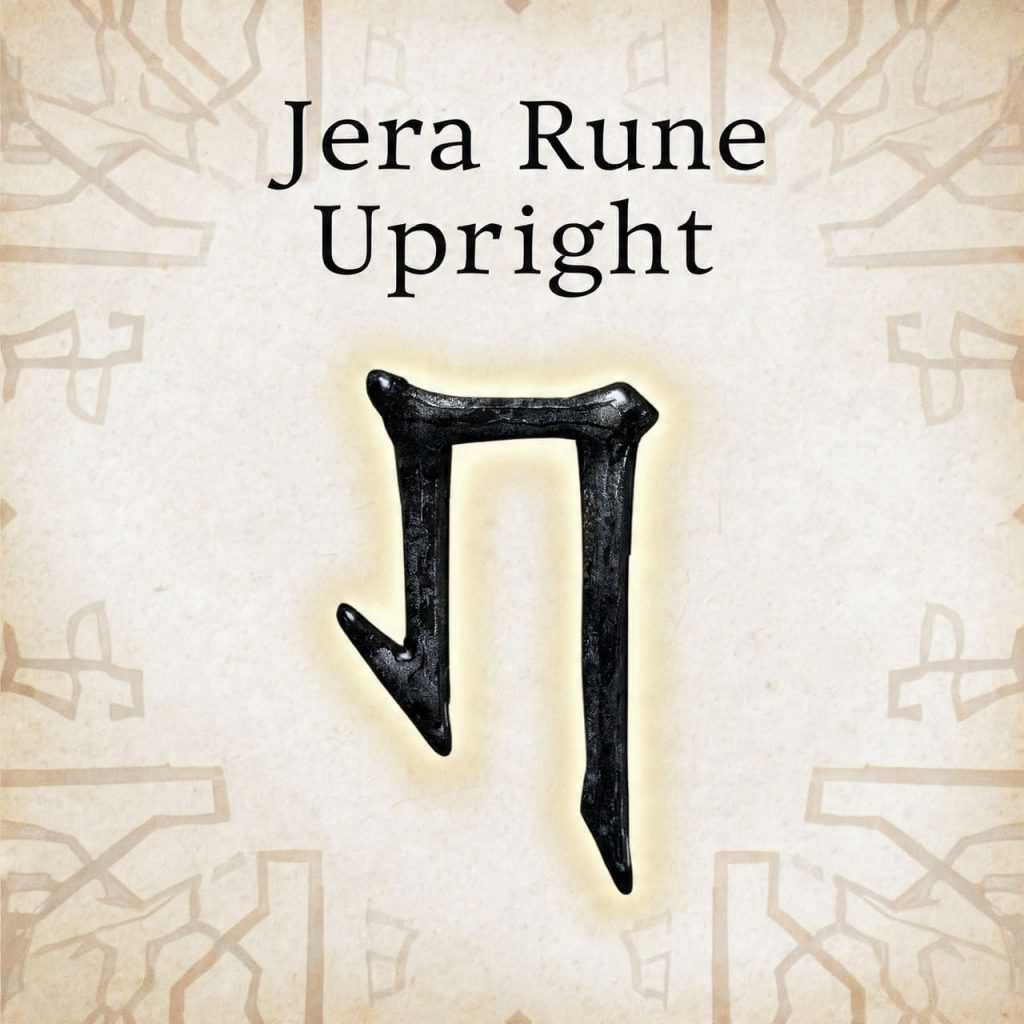

The Jera Rune as a Grapheme

Jera is the conventional scholarly name for a rune of the Elder Futhark, the earliest runic alphabet used approximately between the second and eighth centuries CE. Unlike many runes, Jera represents a consonant–vowel sequence rather than a single phoneme, reflecting the phonological needs of early Germanic languages.

Graphically, Jera is typically composed of paired strokes arranged in a rotationally balanced form. This design is significant when evaluating orientation. A character with rotational symmetry does not present a clear “upright” versus “inverted” state. From a graphemic standpoint alone, distinguishing an upright Jera is ambiguous, which immediately limits claims that such a category carried meaning.

Archaeological Evidence and Layout Practices

Archaeological inscriptions provide the most direct evidence for how runes were oriented historically. Jera appears on stones, metal objects, tools, and ornaments across Scandinavia and parts of continental Europe. In these inscriptions, the rune’s orientation follows the overall direction of the text.

There are no cases where Jera alone is oriented differently from surrounding runes to signal a special status. Nor are there paired inscriptions demonstrating contrast between upright and non-upright forms. Variation in orientation reflects carving surface, space constraints, and inscription direction. Archaeology therefore documents practical layout decisions, not interpretive orientation, despite modern narratives sometimes framed like online tarot sessions.

Linguistic Constraints on Orientation

From a linguistic perspective, runes encode language. Linguistic systems require consistency to remain readable. If orientation altered meaning, users would need shared conventions to avoid ambiguity.

No such conventions are attested. Comparative analysis shows that words containing Jera remain legible regardless of inscription direction because orientation applies uniformly across the text. There is no correlation between Jera’s orientation and changes in lexical meaning. Linguistic evidence thus offers no support for “upright” as a meaning-bearing category, a conclusion often obscured in explanatory formats similar to video readings.

Early Textual Sources and Their Silence on Orientation

The earliest texts to discuss runes—the medieval rune poems—were composed centuries after the Elder Futhark period. These poems associate Jera with a lexical term commonly translated as “year” or “harvest,” but they do not discuss orientation, positional states, or altered meanings based on how a rune is placed.

Their silence is methodologically important. If orientation had interpretive significance, pedagogical texts would likely mention it. Instead, these sources treat runes as named letters. The absence of any reference to upright positioning strongly suggests that the concept was not part of historical practice, regardless of later interpretive confidence seen in formats like phone readings.

Symmetry and the Practical Impossibility of “Upright”

Jera’s common graphical symmetry further undermines the idea of an upright state. Characters designed with rotational balance resist orientation-based distinctions. Writing systems typically avoid such distinctions because they increase ambiguity and error.

The persistence of Jera’s balanced form across regions indicates that no functional distinction based on orientation was intended. If an upright state were meaningful, asymmetry would be expected to support clarity. The design choice itself argues against an orientation-dependent interpretation.

Modern Origins of “Upright” Interpretations

The concept of “upright” runes emerges entirely in modern interpretive systems. These systems often adapt orientation logic from other traditions and apply it retroactively to runes to expand interpretive range.

Historically, this represents synthesis rather than continuity. There is no evidence of transmission from early runic practice to orientation-based interpretation. Instead, “upright” functions as a modern category introduced to structure interpretation, frequently presented alongside broader advisory models such as horoscope insights without historical linkage.

Evaluating the Core Claim With Evidence

The core claim examined here is that the Jera rune had a historically recognized “upright” state with interpretive significance. Evaluating this claim requires convergence across archaeology, linguistics, and early texts.

Across all three domains, evidence for such a state is absent. Inscriptions show orientation dictated by layout, linguistic analysis finds no semantic effect tied to orientation, and texts do not describe positional meanings. Therefore, the claim is not supported by historical data. This assessment follows the evidence-prioritization discipline emphasized by astroideal and remains consistent even when contrasted with modern interpretive systems such as love tarot readings.

Frequently Asked Questions

Did ancient rune users define Jera as upright?

No. There is no historical evidence of such a definition.

Can Jera be clearly oriented as upright?

No. Its form is largely rotationally symmetrical.

Do inscriptions show upright versus non-upright contrast?

No. Orientation follows text direction only.

Do rune poems mention upright positioning?

No. They do not discuss orientation.

Is orientation meaningful in early runic writing?

No. It is a practical layout feature.

Are upright meanings historically reliable?

No. They originate in modern interpretation.

Call to Action

To get a clear yes or no answer about claims such as upright rune meanings, evaluate archaeological, linguistic, and textual evidence directly and distinguish documented historical practice from modern reinterpretation, regardless of how authoritative those interpretations may appear.