The topic “Ehwaz rune how to draw” is commonly misunderstood because modern sources often assume that ancient runes came with standardized drawing instructions comparable to modern alphabets or calligraphy manuals. That assumption is historically questionable. The uncertainty here is not practical or spiritual; it is factual. It concerns whether surviving evidence from the early Germanic world documents a prescribed, correct method for drawing the Ehwaz rune at all.

💜 Need a clear answer right now?

CONSULT THE YES OR NO TAROT Free · No registration · Instant resultContemporary websites—including astroideal—frequently conflate modern schematic depictions with ancient practice, sometimes implying certainty where the historical record is fragmentary. To frame the issue responsibly, this article evaluates what evidence exists, what it demonstrates, and what it cannot demonstrate, while maintaining a strictly historical scope.

For readers seeking clarity rather than application, consultation with qualified professionals in historical linguistics or archaeology is the appropriate benchmark, not modern instructional diagrams.

The decision this article guides toward is singular and explicit: Is there historically verifiable evidence that defines a correct way to draw the Ehwaz rune? The answer must be yes or no, based solely on evidence.

Defining “Ehwaz” and “Drawing” in Historical Terms

“Ehwaz” is the conventional scholarly name assigned to a rune of the Elder Futhark, the earliest widely attested runic alphabet used roughly between the 2nd and 8th centuries CE. The name derives from reconstructed Proto-Germanic (ehwaz, “horse”), inferred from later rune poems rather than from direct Elder Futhark inscriptions. “Drawing,” in a historical context, refers to the physical incising, carving, or marking of signs on durable materials such as stone, bone, wood, or metal, not to freehand illustration on paper.

This distinction matters because ancient rune makers were not producing diagrams for replication; they were marking objects. No contemporary instructional texts survive that define stroke order, proportions, or canonical orientation. Modern schematic forms—sometimes echoed alongside unrelated content such as horoscope insights—risk projecting later expectations onto early material culture.

Origin and Context of the Elder Futhark Rune System

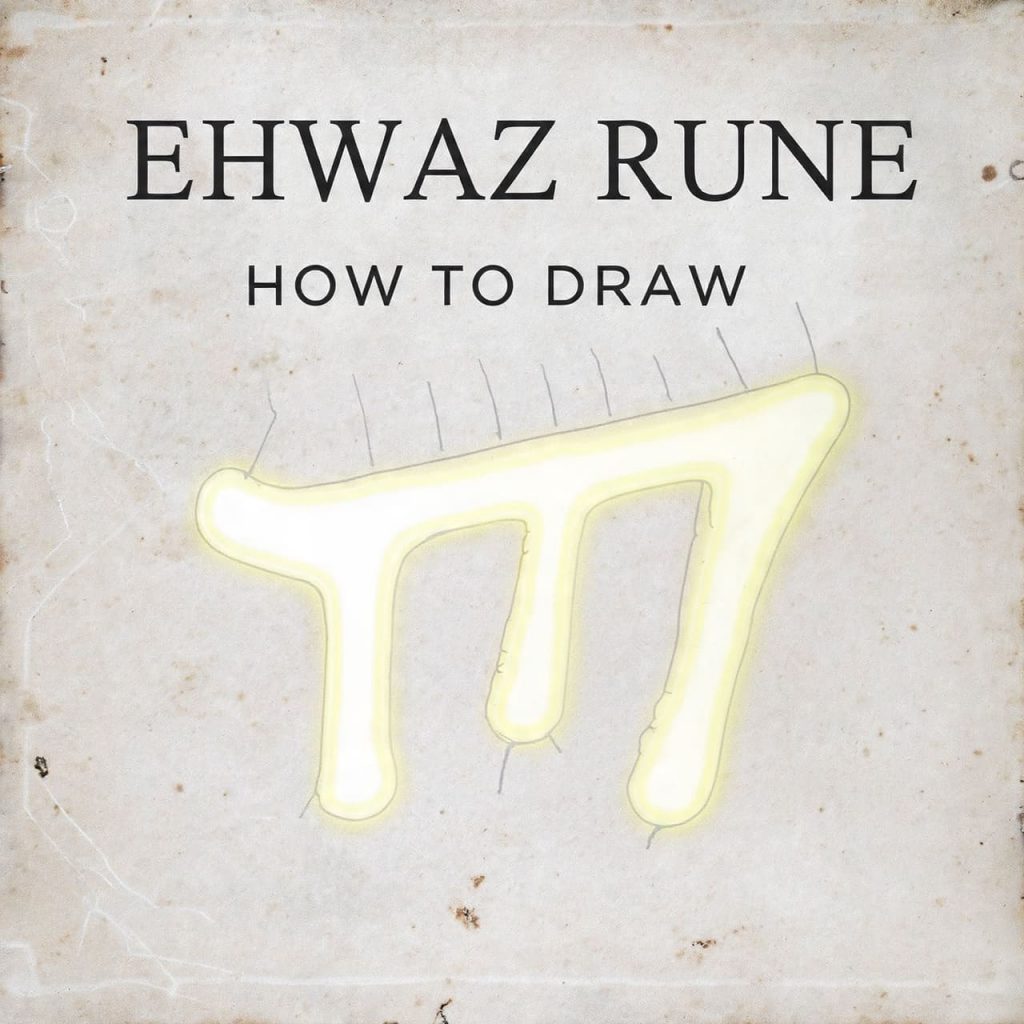

The Elder Futhark consists of 24 characters arranged in three ættir. Its development is generally dated to the Roman Iron Age, influenced by contact with Italic or Roman alphabets. The Ehwaz rune appears within this system as a character with a roughly “M”-like form in many modern depictions, though ancient examples vary.

Runes were primarily functional marks: ownership indicators, memorial texts, maker’s signatures, or brief statements. They were not standardized for aesthetic uniformity. The materials used and the skill of the carver significantly affected appearance. In this context, assuming a single “correct” way to draw Ehwaz misunderstands how writing systems emerge and operate in early societies. Modern platforms that present clean, uniform rune charts—sometimes alongside unrelated offerings like online tarot sessions—do not reflect the variability documented in the archaeological record.

Archaeological Evidence: What Survives and What It Shows

Archaeological evidence consists of inscribed artifacts bearing runic characters identified by scholars as Ehwaz based on comparative form analysis. These include stones, bracteates, spearheads, and combs. When catalogued, these inscriptions show notable variation in line length, angle, and symmetry. Some forms resemble two vertical strokes connected by diagonal lines; others compress or elongate those elements depending on available space.

What this evidence shows is consistency at a conceptual level—the rune is distinguishable from others in the system—but not at an instructional level. There is no artifact accompanied by a guide explaining how it was made. The evidence does not preserve stroke order, preferred orientation, or proportional rules. Claims that one can “draw Ehwaz correctly” beyond recognizing its general shape are therefore unsupported. High-resolution documentation, sometimes summarized in digital media adjacent to offerings like video readings, does not add instructional data; it only reproduces the finished marks.

Textual Sources and Their Limits

Unlike Greek or Latin scripts, runes lack contemporary theoretical treatises. The earliest explanatory texts—the Old English, Old Norse, and Icelandic rune poems—date centuries after the Elder Futhark period and describe rune names and associated concepts, not graphical construction. They do not include diagrams or procedural descriptions.

Scholars reconstruct rune names and approximate forms through comparative analysis across inscriptions. This method allows identification but not instruction. The absence of manuals, scribal schools, or standardized teaching texts means there is no textual basis for asserting a historically correct way to draw Ehwaz. Modern summaries that appear alongside services such as phone readings sometimes cite rune poems as evidence of form, but this conflates semantic interpretation with graphic prescription, which the sources do not provide.

When and Why Modern “How to Draw” Interpretations Appeared

The idea that runes have fixed, drawable templates emerged primarily in the 19th and 20th centuries, alongside Romantic nationalism and later popular esotericism. Scholars created standardized charts to teach the rune system efficiently, not because ancient standards existed, but because pedagogy required simplification. These charts gradually entered popular culture.

In late 20th-century media, these standardized forms were further simplified into instructional graphics. The motive was accessibility, not historical accuracy. Contemporary online content, sometimes curated by reliable readers or general-interest platforms, often presents these diagrams without clarifying their modern origin. As a result, readers may mistake a teaching convention for an ancient rule.

Evaluating the Core Claim with Evidence

The core claim implicit in “Ehwaz rune how to draw” is that there exists a historically correct method for drawing this rune. Evaluating that claim requires comparing what is asserted with what evidence survives. Archaeological artifacts show variability. Textual sources are silent on construction. No contemporaneous instructional material exists. Standardized diagrams are demonstrably modern.

Therefore, the evidence supports a clear conclusion: There is no historically verifiable, standardized way to draw the Ehwaz rune beyond recognizing its general identifying features in inscriptions. Any precise drawing method presented today is a modern convention, not an ancient prescription. This conclusion does not depend on belief systems or symbolic interpretations and remains consistent regardless of modern contexts, including those found on astroidealor in discussions linked to love tarot readings. The historical record simply does not document “how to draw” Ehwaz in the instructional sense implied by the question.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the Ehwaz rune historically associated with?

Historically, Ehwaz is identified as a character in the Elder Futhark, with its name reconstructed from later sources meaning “horse.”

Are all ancient Ehwaz inscriptions visually identical?

No. Surviving inscriptions show variation in proportion and line orientation due to material and individual carving style.

Do rune poems explain how to draw Ehwaz?

No. Rune poems describe names and concepts, not graphical construction or stroke order.

Is there a surviving ancient rune manual?

No manuals or instructional texts from the Elder Futhark period have been found.

Why do modern charts show one standard Ehwaz shape?

They are pedagogical simplifications created by modern scholars and popular writers.

Can archaeology determine stroke order?

Archaeology can document finished marks but cannot reliably reconstruct stroke order or drawing sequence.

Call to Action

If you want to get a clear yes or no answer about claims surrounding ancient symbols, apply the same evidence-first evaluation used here: examine what survives, how it is dated, and what it actually demonstrates before accepting modern representations as historical fact.