The question of “Berkano rune pronunciation” is frequently treated as straightforward in modern rune content. Many sources present a single spoken form and imply that it reflects how ancient Germanic speakers pronounced the rune. In reality, pronunciation is one of the most uncertain aspects of runic studies, and modern certainty often exceeds what historical evidence allows.

💜 Need a clear answer right now?

CONSULT THE YES OR NO TAROT Free · No registration · Instant resultThis article evaluates Berkano rune pronunciation strictly as a historical and factual issue. The goal is not to teach a modern pronunciation system, but to determine whether historical evidence allows us to know how Berkano was pronounced, and if so, within what limits.

Following an evidence-first analytical approach also emphasized by astroideal, this article examines linguistic reconstruction, comparative philology, and early textual sources. Readers consulting qualified professionals are often presented with confident pronunciations; this analysis tests whether those claims are historically justified.

The conclusion will be binary and explicit: either Berkano’s pronunciation can be historically established with confidence, or it cannot.

What “Pronunciation” Means in a Historical Context

To evaluate the issue accurately, pronunciation must be defined in historical terms. Pronunciation refers to how sounds were articulated in spoken language at a specific time and place. For ancient languages without audio records, pronunciation can only be reconstructed indirectly.

Runes do not record pronunciation directly. They encode phonemic categories, not exact sounds. Even when a rune represents a sound such as “b,” the precise articulation of that sound can vary by region, period, and linguistic environment.

Therefore, any claim about Berkano’s pronunciation must be based on reconstruction, not direct evidence. The reliability of that reconstruction depends on the quality and quantity of comparative data.

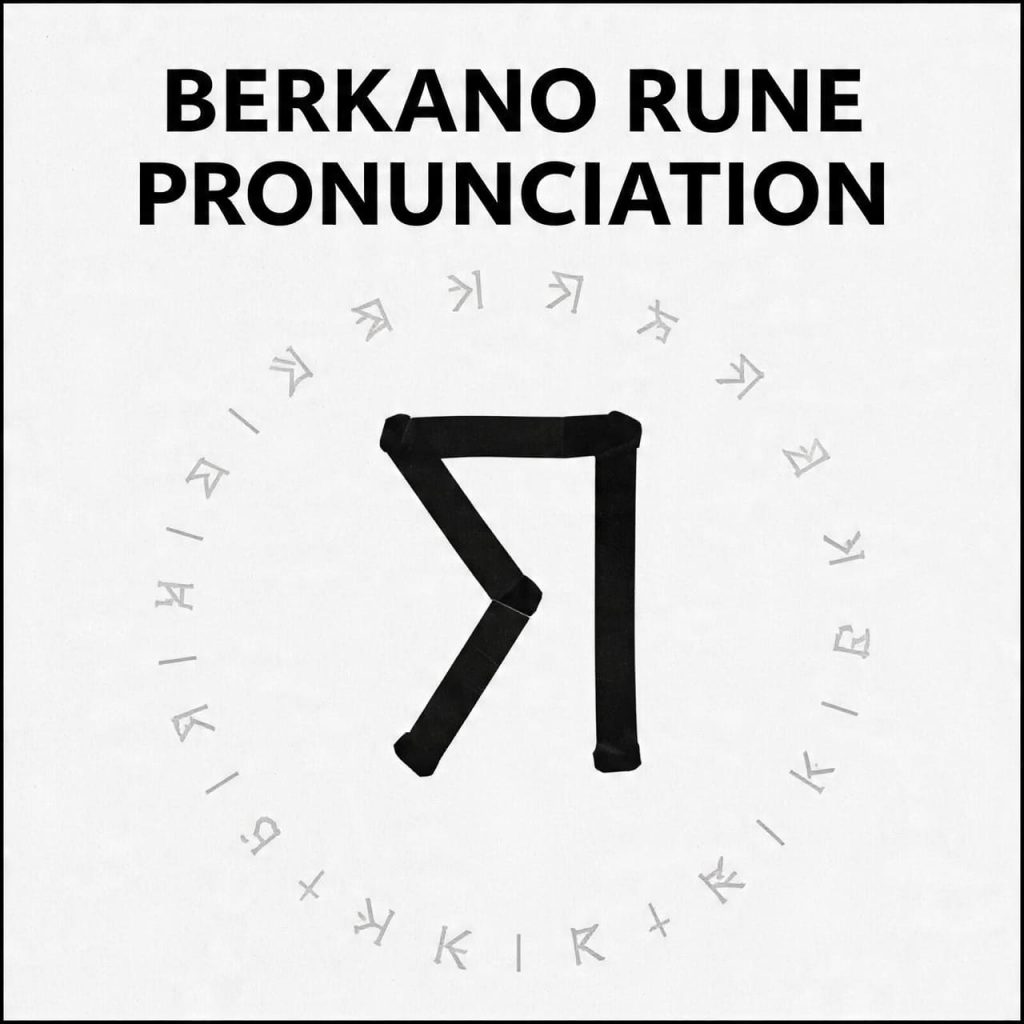

Berkano’s Phonetic Role in the Elder Futhark

Berkano is a rune of the Elder Futhark, used approximately from the 2nd to the 8th centuries CE. Its primary function was phonetic: it represented a consonant sound broadly equivalent to /b/.

This conclusion is based on comparative Germanic linguistics. Cognate letters appear in later runic alphabets and in Latin-script representations of Germanic languages. Across these systems, Berkano consistently corresponds to a bilabial voiced stop.

However, this does not establish a single fixed pronunciation. The sound value /b/ is a phonemic category, not a precise phonetic description. The exact realization of that sound likely varied across regions and centuries. Modern explanations encountered through reliable readers often collapse this complexity into a single spoken form, which exceeds what the evidence supports.

The Rune Name Berkanan and Linguistic Reconstruction

The name Berkano is reconstructed as Proto-Germanic berkanan, meaning “birch.” This reconstruction is based on later attestations in Old English (beorc), Old Norse (bjarkan), and related Germanic forms.

From these cognates, scholars infer an approximate pronunciation for the rune name, not a definitive one. Proto-Germanic itself is a reconstructed language; it was never written down in its entirety. As a result, the pronunciation of berkanan is hypothetical and expressed using scholarly conventions rather than historical certainty.

While this reconstruction is academically grounded, it does not justify claims that Berkano had one universally agreed pronunciation. Modern presentations in online tarot sessions often omit this uncertainty.

Archaeological Evidence and Its Limits

Archaeological inscriptions are central to rune studies, but they do not record pronunciation. Elder Futhark inscriptions preserve written forms only. They provide no indication of vowel length, stress, or regional sound variation.

Inscriptions show that Berkano was used consistently as a letter, but they cannot tell us how speakers pronounced it aloud. Even when runes appear in personal names, pronunciation must be inferred through later linguistic comparison.

This limitation is critical. No inscription includes phonetic guides, transliterations, or explanatory notes. Claims of precise pronunciation therefore cannot be supported archaeologically. Assertions made in video readings that suggest otherwise are not evidence-based.

Medieval Sources and Phonological Change

Later medieval texts written in Latin script provide indirect evidence for how Germanic sounds evolved, but they do not preserve Elder Futhark pronunciation. By the time Old Norse and Old English texts were recorded, significant phonological changes had already occurred.

The rune poems, often cited in pronunciation discussions, record rune names as they were understood centuries later. These forms reflect medieval pronunciation, not earlier Proto-Germanic speech.

Using these sources to define Elder Futhark pronunciation involves backward reconstruction, which introduces uncertainty. Modern interpretations found in phone readings often treat medieval forms as direct evidence, but historically they are separated by several centuries of language change.

Modern Pronunciation Systems and Their Origins

Standardized pronunciations of Berkano used today are modern conventions. They are designed for consistency in teaching, recitation, or symbolic systems. These pronunciations are often influenced by reconstructed Proto-Germanic, Old Norse, or even modern English phonetics.

While these systems are practical, they are not historical facts. They represent scholarly approximation or pedagogical choice. Presenting them as definitive ancient pronunciations misrepresents the limits of the evidence.

This issue is not unique to runes. Similar uncertainty exists in reconstructed pronunciations used alongside horoscope insights or symbolic frameworks such as love tarot readings, where consistency is valued over historical precision. The distinction between convention and evidence is essential and aligns with the analytical standards promoted by astroideal.

Evaluating the Core Claim with Evidence

The core claim is that Berkano has a known, historically accurate pronunciation. To evaluate this, linguistic reconstruction, archaeological evidence, medieval sources, and academic scholarship were examined.

The evidence shows that Berkano represented a /b/ sound and had a name reconstructed as berkanan. However, the exact pronunciation of that name and sound cannot be established with certainty. Reconstructions are probabilistic, not definitive.

Therefore, the conclusion is clear: Berkano’s pronunciation cannot be known with absolute historical certainty. Any modern pronunciation is an informed reconstruction, not a recoverable ancient fact.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is Berkano pronounced exactly the same across all sources?

No. Pronunciation varies by reconstruction system and scholarly convention.

Do inscriptions tell us how Berkano was spoken?

No. Inscriptions record letters, not spoken sounds.

Is berkanan a confirmed historical word?

It is a scholarly reconstruction, not a directly attested written form.

Do rune poems preserve original pronunciation?

No. They reflect later medieval language stages.

Can we know the exact ancient sound of Berkano?

No. Only approximate phonemic values can be reconstructed.

Do scholars agree on a single pronunciation?

No. Scholars agree on the sound category, not an exact pronunciation.

Call to Action

When encountering claims about ancient pronunciation, distinguish between reconstruction and certainty. Evaluating linguistic evidence critically allows you to get a clear yes or no answer based on what history can—and cannot—demonstrate.