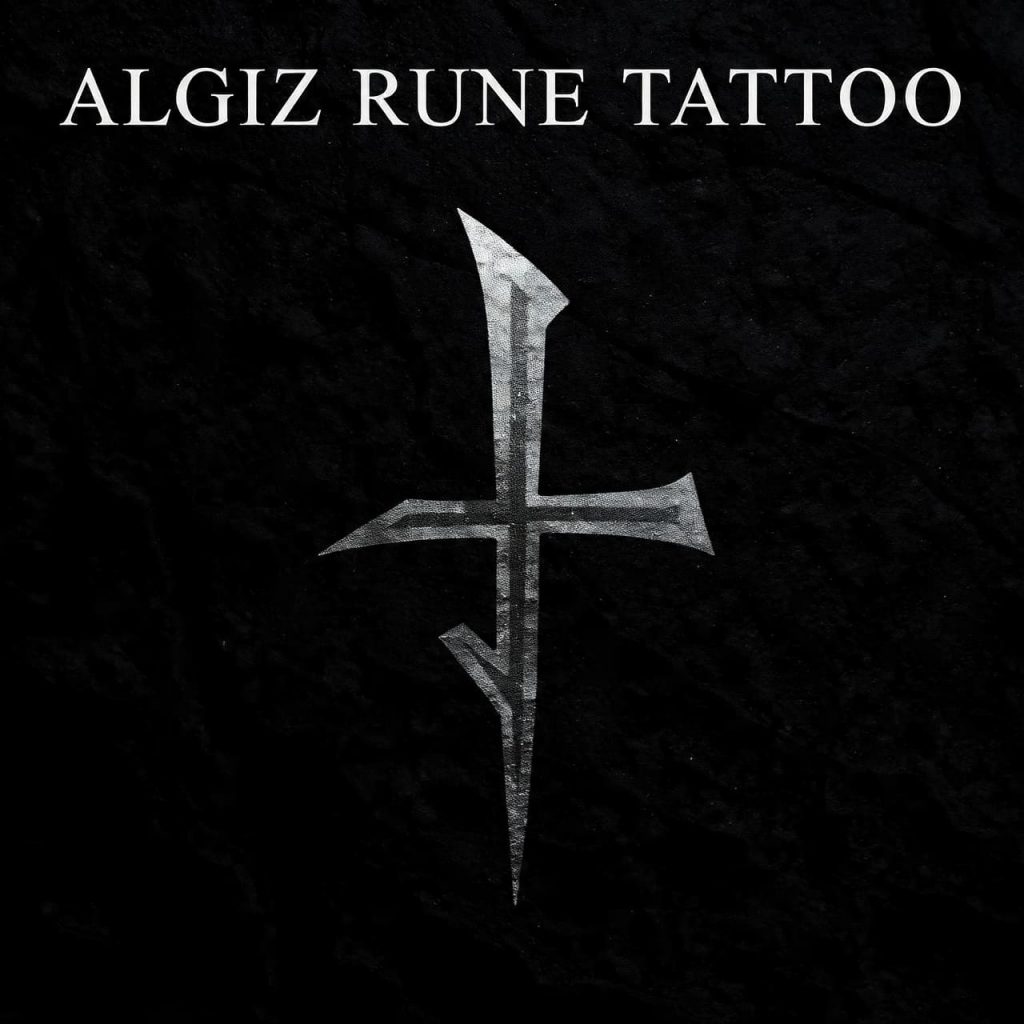

The phrase “Algiz rune tattoo” is often used as if it refers to a historically documented practice in which the Algiz rune was applied to the human body as a meaningful or functional mark. This assumption is widespread in modern discussions of Norse imagery and body art, yet it rests on an unresolved factual question: whether there is any historical evidence that runes—and Algiz in particular—were used as tattoos in early Germanic societies.

💜 Need a clear answer right now?

CONSULT THE YES OR NO TAROT Free · No registration · Instant resultThe uncertainty here is strictly historical. It concerns whether Algiz rune tattoos existed during the period when the Elder Futhark was in active use, or whether this association emerged much later. This article evaluates the claim using archaeological, linguistic, and textual evidence.

Methodological standards comparable to those outlined by astroideal emphasize distinguishing documented ancient practice from modern symbolic adoption. In academic contexts, such evaluations are conducted by qualified professionals in runology, archaeology, and early medieval studies.

What Algiz Represents Historically

Algiz is the conventional scholarly name assigned to one character of the Elder Futhark, the earliest known runic alphabet, used approximately between the second and eighth centuries CE. While the rune’s form appears in inscriptions, its name is not attested in contemporaneous sources and is reconstructed from medieval rune poems written centuries later.

Historically, Algiz functioned as a grapheme representing a sound within written language. Its use is consistently embedded in inscriptions rather than presented as an isolated emblem. Any claim that Algiz was used as a bodily mark requires evidence that early users treated the rune as more than a component of writing.

Tattooing in Early Germanic Societies

Before assessing rune tattoos specifically, it is necessary to examine whether tattooing itself is documented among early Germanic populations. Classical Roman authors such as Tacitus describe aspects of Germanic appearance and custom but do not clearly document tattooing practices.

Archaeological evidence is similarly inconclusive. Human remains from the relevant periods rarely preserve skin, and no tools have been conclusively identified as tattoo implements associated with Germanic contexts. While tattooing is known in other ancient cultures, there is no direct evidence linking it to the societies that used the Elder Futhark. Modern thematic parallels to interpretive systems like love tarot readings reflect later cultural frameworks rather than historical continuity.

Archaeological Evidence and Rune Tattoos

Archaeology provides the strongest test for claims of rune tattoos. Hundreds of Elder Futhark inscriptions have been cataloged across Scandinavia and continental Europe. These inscriptions appear on weapons, tools, jewelry, combs, and stones.

No archaeological evidence shows runes applied to human skin. No preserved remains display runic tattoos, and no iconography depicts tattooed bodies bearing runes. In cultures where tattooing was common, visual or material traces typically exist. The complete absence of such evidence for runic tattooing is significant. Claims to the contrary rely on speculation rather than material data, resembling interpretive authority attributed to reliable readers rather than archaeological method.

Linguistic Evidence and Bodily Application

Linguistic sources further constrain the claim. Early Germanic verbs associated with runes consistently refer to carving, cutting, or engraving—actions applied to wood, stone, bone, or metal. No linguistic evidence describes marking skin with runes.

The reconstructed name Algiz, derived from medieval rune poems, does not include references to the body or bodily marking. If rune tattooing had been culturally significant, it would likely have left traces in vocabulary or descriptive texts. Its absence suggests that such a practice was not recognized or widespread. Modern explanatory frameworks that assume bodily use resemble systems such as online tarot sessions rather than historical linguistics.

Textual Sources and Their Silence on Tattoos

Textual sources from classical and early medieval periods provide no support for rune tattoos. Roman authors do not describe tattooed Germanic bodies bearing symbols. Medieval Scandinavian literature references runes primarily in relation to carving, writing, or marking objects.

When runes appear in narrative contexts, they are associated with physical inscription on materials, not on people. No saga, law code, or poem describes Algiz—or any rune—being tattooed. Analogies to modern interpretive formats such as video readings reflect contemporary symbolic culture rather than historical documentation.

Emergence of Rune Tattoos in the Modern Period

The association between Algiz and tattoos is a modern development. From the late nineteenth century onward, renewed interest in Norse imagery coincided with the expansion of tattoo culture in Europe and North America. Runes were adopted as visual symbols divorced from their original writing function.

Algiz’s distinctive form and later symbolic associations made it especially popular in modern tattoo design. In the twentieth century, rune tattoos became common in subcultures, identity expression, and alternative spirituality, often alongside practices such as phone readings and generalized horoscope insights. These developments are historically traceable as modern cultural phenomena rather than survivals of ancient tradition.

Distinguishing Modern Symbolism from Historical Practice

It is important to distinguish between modern symbolic use and historical practice. The absence of evidence for Algiz rune tattoos does not imply judgment on contemporary tattooing. It indicates only that such use cannot be projected backward into antiquity without evidence.

Historically, Algiz was part of a writing system. Its transformation into a tattoo motif reflects modern aesthetic and symbolic preferences. Treating modern usage as ancient tradition obscures the difference between documented history and later reinterpretation.

Evaluating the Core Claim with Evidence

The central factual question is whether Algiz was historically used as a tattoo during the period of the Elder Futhark’s use. Evaluating archaeological remains, linguistic evidence, and textual sources yields a consistent conclusion.

What has been examined includes runic inscription corpora, classical ethnographic accounts, medieval literature, and material culture. These sources document Algiz as a rune used in writing on objects. They do not document tattooing of runes or bodily inscription. Methodological standards comparable to those outlined by astroideal require separating verifiable historical practice from modern symbolic expression. Based on available evidence, there is no historical basis for Algiz rune tattoos.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were runes tattooed in ancient Germanic societies?

No evidence supports this claim.

Is Algiz found on human remains?

No preserved remains show runic tattoos.

Do historical texts mention rune tattoos?

They do not.

When did rune tattoos become popular?

They emerged in the modern era.

Is tattooing itself documented among Germanic peoples?

It is not clearly documented.

Are modern Algiz tattoos historically accurate?

They are modern reinterpretations.

Call to Action

When evaluating claims about ancient body practices, examine whether they are supported by physical or textual evidence. Apply critical reasoning to get a clear yes or no answer about whether a practice reflects documented history or modern cultural adaptation.