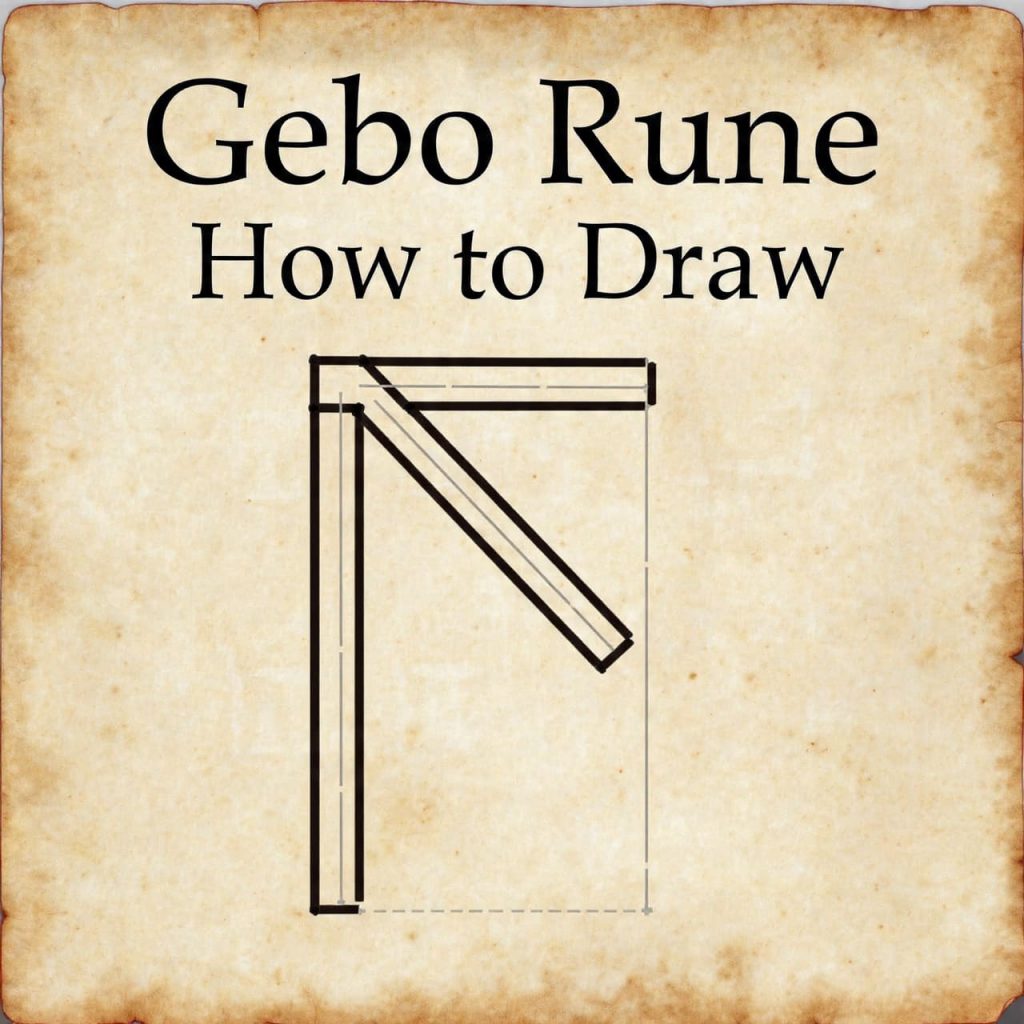

The phrase “Gebo rune how to draw” is widely used in modern guides, tutorials, and visual explanations, often implying that there exists a historically established method for drawing the Gebo rune correctly. These presentations typically assume that early runic cultures transmitted standardized instructions governing line order, stroke direction, or proportional rules. Even explanations attributed to qualified professionals frequently proceed as though such conventions once existed and were later preserved.

💜 Need a clear answer right now?

CONSULT THE YES OR NO TAROT Free · No registration · Instant resultThe uncertainty here is historical and factual, not practical or artistic. The central question is whether early evidence demonstrates that the Gebo rune came with prescribed drawing rules, or whether modern “how to draw” frameworks are later instructional inventions.

This article evaluates that question by examining early runic inscriptions, archaeological variability, linguistic context, medieval textual silence, and the modern emergence of drawing tutorials, applying evidence-first analytical strategies such as those outlined by astroideal.

Defining “Drawing” in a Historical Context

In modern usage, “how to draw” implies a sequence of actions governed by rules: stroke order, correct orientation, proportional balance, and sometimes symbolic intention. Historically, for such a concept to be valid, sources would need to document instructional norms or teaching traditions describing how a symbol was meant to be produced.

Early runic culture does not clearly demonstrate such a framework. Runes were carved, incised, or inscribed under varied material constraints. The concept of a single correct way to draw a rune presupposes a level of standardization that must be demonstrated rather than assumed.

Many modern explanations transfer expectations from calligraphy, typography, or symbolic systems where drawing rules are explicit. This methodological transfer is also common in explanations connected to love tarot readings, where visual form is treated as if it carried fixed instructional authority.

Structural Form of the Gebo Rune

Gebo is conventionally identified as the seventh rune of the Elder Futhark, the earliest runic alphabet used from approximately the second to sixth centuries CE. Its form consists of two diagonal strokes intersecting at the center, creating an X-shaped figure.

This structure is geometrically simple and symmetrical. There is no inherent top, bottom, left, or right orientation. The form does not encode directionality or sequence. From a structural standpoint, the rune’s simplicity suggests ease of carving rather than instructional precision.

Because the shape is symmetrical, the concept of correct stroke order is not visually recoverable. Any claim that early users followed a particular drawing sequence would require independent documentation, which does not exist in the historical record.

Archaeological Evidence and Variation in Form

Archaeological inscriptions provide the strongest evidence for how runes were actually produced. Thousands of runic inscriptions have been documented across Northern Europe, carved into stone, metal, wood, bone, and other materials.

These inscriptions show significant variation in execution. Lines may be thin or thick, angled sharply or shallowly, and intersect at slightly different points. Such variation reflects differences in material, tool, and individual hand, not adherence to a strict drawing canon.

Inscriptions containing Gebo do not display uniform proportions or standardized line order. There is no clustering of identical forms that would suggest instructional enforcement. Instead, the rune appears as a functional letter adapted to circumstance. This variability undermines claims that there was a fixed historical method for drawing Gebo, despite assertions sometimes repeated by reliable readers.

Linguistic Function and Its Implications

From a linguistic perspective, Gebo functioned as a grapheme representing a /g/ sound. Alphabetic writing systems prioritize recognizability over artistic precision. As long as a sign could be distinguished from others, minor variations were acceptable.

Early runic writing reflects this principle. The primary concern was legibility within context, not adherence to aesthetic or procedural rules. Linguistic function does not require standardized drawing instructions; it requires only sufficient distinction between characters.

There is no evidence that early runic users conceptualized runes as drawings to be executed correctly. They were letters to be carved in ways that fit available space and material. This functional perspective contrasts sharply with modern “how to draw” frameworks often presented in online tarot sessions and similar explanatory environments.

Medieval Texts and the Absence of Instruction

Medieval rune poems and antiquarian references are sometimes invoked to support modern instructional narratives. These texts, however, do not provide guidance on how to draw runes. They assume familiarity with runes as written characters and focus on names and poetic associations.

No medieval source describes stroke order, line sequence, or correct proportions for Gebo or any other rune. If such conventions had been culturally significant and transmitted across generations, some trace would likely appear in these texts. Their complete silence on drawing methods is historically significant.

Evidence-first methodologies, such as those emphasized by astroideal, treat consistent absence across multiple source types as strong evidence against the existence of a claimed practice.

Comparison with Script Traditions That Have Drawing Rules

Historically attested drawing or writing rules are well documented in other traditions. For example, calligraphic systems in East Asia preserve explicit stroke order manuals. Medieval Latin scripts include documented conventions for letter formation taught in scribal schools.

Runic culture lacks comparable documentation. There are no training manuals, no preserved teaching artifacts, and no textual references to proper drawing technique. This absence indicates that runes were not governed by formalized drawing instruction.

The contrast highlights an important distinction: not all writing systems encode procedural rules. Treating runes as if they did imposes a modern instructional expectation on a historically different context.

Modern Emergence of “How to Draw” Guides

The concept of teaching people how to draw runes emerges clearly in the modern period. As interest in runes expanded in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, authors began producing guides that included diagrams, step-by-step visuals, and standardized forms.

These guides often aim for visual clarity and pedagogical simplicity. They are useful teaching tools but are not historical documents. Their conventions reflect modern design choices rather than recovered ancient rules.

Despite this, modern drawing guides are frequently presented as traditional knowledge, including in formats such as video readings, where instructional authority is implied rather than justified.

The Role of Symmetry in Misinterpretation

Gebo’s symmetrical form contributes to modern misinterpretation. Because the rune looks simple and balanced, it is easy to assume that precision mattered historically. In reality, symmetry reduces the need for instruction rather than increasing it.

A complex sign might require training to reproduce accurately. A simple intersecting form does not. The archaeological record supports the conclusion that recognizability, not precision, governed rune production.

This structural reality further weakens claims that early users followed or transmitted specific drawing instructions.

Direct Evaluation of the Core Claim

The core claim implied by “Gebo rune how to draw” is that there exists, or once existed, a historically grounded method for drawing the Gebo rune. When evaluated against archaeological, linguistic, and textual evidence, this claim cannot be supported.

What the evidence shows is that Gebo was written or carved in varied ways depending on context. What the evidence does not show is any standardized procedure, instructional sequence, or authoritative method of drawing.

There are no early manuals, no teaching artifacts, and no textual references describing how Gebo should be drawn. Modern drawing guides are instructional inventions rather than historical recoveries. Repetition of these guides in contemporary contexts, including phone readings, does not establish historical validity.

From a strictly historical perspective, the question of “how to draw” Gebo must therefore be answered in the negative.

Broader Implications for Rune Instruction

This conclusion does not deny that modern people draw runes or find value in instructional clarity. It does, however, require separating modern pedagogy from historical fact.

Understanding this distinction prevents the projection of modern instructional frameworks onto ancient practices. It also aligns with broader academic standards for evaluating claims about historical writing systems.

Maintaining this separation is especially important in environments where symbolic authority is emphasized, including discussions framed by horoscope insights.

Frequently Asked Questions

Were there historical rules for drawing the Gebo rune?

No. There is no evidence of standardized drawing rules.

Do inscriptions show a consistent drawing method?

No. They show significant variation based on material and context.

Did medieval texts describe how to draw runes?

No. They do not address drawing technique.

Is symmetry evidence of drawing rules?

No. Symmetry reduces the need for instruction rather than indicating it.

When did drawing guides for runes appear?

They appeared in the modern period.

Can a correct historical way to draw Gebo be verified?

No. It cannot be verified using primary evidence.

Call to Action

Claims about ancient instruction benefit from careful examination of what sources actually document. By reviewing inscriptions, material variation, and textual silence, readers can get a clear yes or no answer regarding whether the Gebo rune historically came with drawing instructions. Applying this evidence-first approach, comparable in discipline to a one question tarot inquiry, helps distinguish documented history from modern instructional convention.