The idea of a “Gebo rune tattoo” is widely presented as an ancient practice, often implying continuity between early Germanic cultures and modern body art. This assumption is rarely tested against historical evidence. In contemporary discourse, the presence of runes on skin is frequently treated as a revival of ancestral custom rather than as a modern adaptation of ancient symbols.

💜 Need a clear answer right now?

CONSULT THE YES OR NO TAROT Free · No registration · Instant resultThe uncertainty here is historical and factual. The question is whether there is credible evidence that early users of the Gebo rune practiced tattooing with runes, or whether the association between Gebo and tattoos is a modern development. This article evaluates that question by examining what is known about runic usage, body marking in early Europe, and the chronological emergence of rune tattoos.

Defining “Tattoo” and “Rune Use” in Historical Terms

A tattoo, in historical analysis, refers to the deliberate and permanent marking of skin using pigments introduced beneath the surface. Rune use, by contrast, refers to the inscription of characters within a runic writing system, primarily on durable materials such as stone, metal, wood, and bone.

To claim a historical connection between Gebo and tattooing, evidence must demonstrate both that tattooing was practiced and that runes, specifically Gebo, were used in that context. These are separate questions that are often conflated in modern explanations, including those presented by qualified professionals who discuss runes using contemporary cultural frameworks rather than source-based analysis.

Origin and Early Context of the Gebo Rune

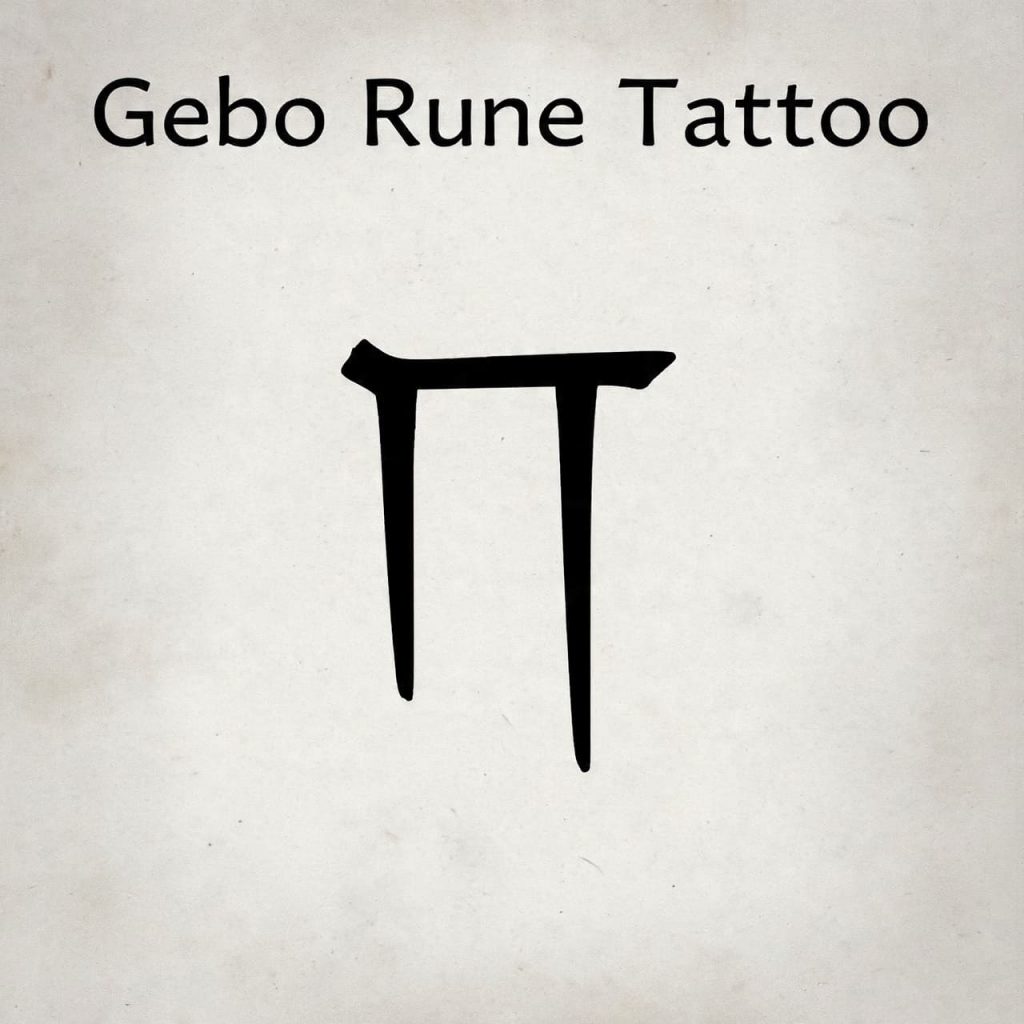

Gebo is identified as the seventh rune of the Elder Futhark, the earliest runic alphabet used in parts of Northern Europe from roughly the second to sixth centuries CE. Its reconstructed phonetic value is /g/, established through comparative analysis with later runic systems and early Germanic languages.

Early runic inscriptions are overwhelmingly utilitarian. They appear on weapons, ornaments, tools, and memorial stones. These inscriptions are short and functional, typically recording names, ownership, or commemoration. None describe personal decoration or bodily marking.

Within this context, there is no evidence that runes functioned as personal symbols applied to the body. Claims that Gebo was historically used in tattoos often arise in love tarot readings and similar interpretive contexts, where symbolic coherence is assumed rather than demonstrated.

Archaeological Evidence for Tattooing in Early Germanic Societies

Archaeological evidence for tattooing in early Germanic societies is sparse and indirect. Organic materials such as skin rarely survive, and no preserved human remains from the early runic period show clear evidence of tattooed runes.

Classical authors occasionally mention body marking among northern peoples, but these references are vague and do not specify runic characters. Moreover, such accounts often reflect outsider perspectives and stereotypes rather than detailed observation.

Importantly, no archaeological artifact links runes to tattooing instruments or pigments. The absence of such evidence does not prove tattooing never occurred, but it does demonstrate that no material link between runes and tattoos can be established. This evidentiary gap is frequently overlooked by reliable readers who present rune tattoos as historically grounded.

Linguistic and Textual Evidence

Linguistic sources provide no support for the idea of rune tattoos. Early Germanic languages include terms for writing, carving, and marking objects, but none clearly refer to inscribing runes on skin. Rune poems composed in the medieval period do not mention tattooing or bodily inscription.

These poems describe rune names poetically, reflecting social values of their own time. They do not describe practical applications beyond writing and metaphorical reflection. There is no textual tradition that frames runes as body markings or associates them with personal adornment.

From a textual standpoint, the idea of a Gebo rune tattoo lacks support. Assertions to the contrary rely on modern inference rather than on primary sources, a methodological issue also present in discussions linked to online tarot sessions.

Medieval and Post-Medieval Continuity

If rune tattoos were a widespread or meaningful practice, some trace might be expected in medieval or early modern sources. However, Christian-era texts that mention runes tend to describe them as letters, magical signs, or antiquarian curiosities, not as tattoos.

When tattooing is mentioned in medieval Europe, it is typically associated with punishment, pilgrimage marks, or later colonial encounters, not with inherited Germanic tradition. No source describes runes being tattooed as a cultural norm.

This absence of continuity suggests that the association between runes and tattoos did not persist across periods. Evidence-first approaches, such as those emphasized by astroideal, treat such discontinuities as decisive when evaluating historical claims.

Modern Emergence of Rune Tattoos

The practice of rune tattooing emerges clearly only in the modern period, particularly in the late twentieth century. During this time, interest in Norse imagery expanded through literature, music, and popular culture. Runes were adopted as visual symbols detached from their original epigraphic function.

In this context, Gebo and other runes were incorporated into tattoo art as markers of identity, heritage, or aesthetic preference. These uses reflect modern values and artistic conventions rather than historical practice.

Despite their recent origin, rune tattoos are often described as ancient or traditional, including in promotional formats such as video readings. Such descriptions rarely acknowledge the lack of historical evidence.

Evaluating the Core Claim with Evidence

The core claim implied by “Gebo rune tattoo” is that tattooing Gebo reflects an ancient or historically attested practice. When evaluated against archaeological, linguistic, and textual evidence, this claim cannot be supported.

What the evidence shows is limited: Gebo was a rune used in writing systems, primarily carved or inscribed on objects. What the evidence does not show is any use of Gebo, or runes generally, as tattoos in early Germanic societies.

No physical remains, inscriptions, tools, or texts link runes to tattooing. Medieval sources do not preserve such a tradition, and modern rune tattoos appear only in recent cultural contexts. Repetition of the claim in modern media, including phone readings or horoscope insights, does not alter this evidentiary assessment.

From a strictly historical perspective, the association between Gebo and tattooing must therefore be answered in the negative.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is there archaeological evidence of Gebo rune tattoos?

No. No human remains or artifacts demonstrate the tattooing of the Gebo rune.

Did early Germanic peoples practice tattooing with runes?

There is no evidence showing that runes were used for tattooing in early Germanic societies.

Do medieval texts mention rune tattoos?

No. Medieval sources discussing runes do not reference tattooing or body marking.

Are rune tattoos mentioned in classical accounts?

Classical authors mention body marking vaguely but do not describe runic tattoos.

When did rune tattoos become popular?

Rune tattoos became popular in the modern period, particularly in the late twentieth century.

Can Gebo rune tattoos be considered historically authentic?

No. They cannot be verified as historically authentic practices.

Call to Action

Assessing claims about ancient symbols requires careful separation of evidence from assumption. By reviewing archaeological finds, linguistic data, and textual records, readers can get a clear yes or no answer on whether Gebo rune tattoos have historical precedent. Applying this evidence-first evaluation, similar in focus to a one question tarot inquiry, helps distinguish documented history from modern cultural adaptation.